Readings from and of Palestine (5)

I started writing this series of posts in early November 2023. I hoped that, in the time it took to compose and share these informal notes about reading, writing, and literature from Palestine, they would become less timely. It’s hard even to put that inchoate hope—whatever it may have been, at different moments in the past three months of horror—into words: that the siege on Gaza would end, hostages and detainees would arrive home, all those displaced from Gaza would get to return... healing, rebuilding, return, renewal? “Restarting the peace process”—phrases like this have been appearing in the news. A beginning to the end of the occupation.

But already even two months ago the scale of the assault on Gaza, the mass destruction of infrastructure and housing, and above all the death of thousands of children, made it impossible to articulate any next phrase. What vision of daily life, resuming, could be superimposed over the gray and bloodied images of bombing’s aftermath we see now whenever we touch our phones? What form, what phrase could come next? Witnessing profound violence incites a profound moral humiliation—that I as a person, representing the possibility of any person, am in a position where my actions fail to have anything like the urgently needed and wanted effect, have failed to help even any one person… I’m left to wonder (we’re left to wonder), do the origins of the world’s horrors lie at the core of the self, like a rot…

What form, what phrase? “Life in Gaza is precious,” the Palestinian writer and psychologist Hala Alyan posted recently on social media, in a graphic in which that phrase simply repeats and repeats. “This premise has only one logical conclusion,” she captions: “#ceasefirenow.” Life is precious, life in Gaza is precious. Those of us who are "book people know that books represent people, books are by and for people. Books represent the possibilities of form, and we need form: the beginnings of a language that could be shared into an urgently needed unknowable common future. The beginnings of the end of the unspeakable. What form is there for a hospital that will never be bombed, that exists in a world where hospitals will never be bombed? A book is part of whatever comes after this question, integral. Life is precious. I haven’t read enough books or known enough people, and right now, in this world, people are being removed from life, from their and our knowing, from all future possibility, at a rate that cannot be thought.

Please accept my gratitude for what the writers below, and all those who read their work, and all those I didn’t manage to list here, have been trying and keep trying to do. Their efforts are beautifully particular and so may resist generalization. But we can say: in such acts of writing and reading, we refuse to give up the search for a form in which life is known as precious, particular, possible, shared.

DEAR GOD, DEAR BONES, DEAR YELLOW

Noor Hindi

Poetry. Haymarket Books, 2020

Those who are here in Northeast Ohio may know Noor’s work, and Noor—she’s from Akron, she attended the NEOMFA Program (Cleveland State University is one of four universities comprising the NEOMFA). When I picture her book in my mind, it is somehow luminous, shining, with the brightness and sharpness of Noor’s insight and aliveness, the terrific indelible blast of the color yellow, sunflowers and sun. You may know her poem “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying”: “One day, I’ll write about the flowers like we own them.” I wish you all could have been (some of you were) at a reading here in Cleveland in February 2023, where Noor read with Shelley Feller (author of the great Dream Boat). The CSU Poetry Center’s reading series (which I get to host) is an array of brightly special nights, of living literature, people gathered around poetry, talking in the bar afterward. Yet the distinctness of each reading, how much I value each of them and how non-interchangeable they are, each created so particularly by the writers and their voices, their gestures, their phrasings and tones, what they are shaping language into and toward. One wonder of poetry: to witness how much someone is themself. In a moment when they are making something out of shared material (language) and to be shared (poetry): you are invited. Shelley’s and Noor’s reading, its free vulnerable humor and power, its open warm inventive language for queer desire, for a free Palestine, an hour of free language, was magnificent. I wish it for everyone and for a world that is like that.

TETHERED TO STARS

FOOTNOTES IN THE ORDER OF DISAPPEARANCE

TEXTU

& more

Fady Joudah

Poetry. Milkweed & Copper Canyon Press, various years

I hope people reading this may already know the work of Fady Joudah, Palestinian American poet, translator, physician. I hope you may have been reading his poems and essays as they have appeared in recent weeks, in recent years, recent decades. Perhaps you know, or now will know, “Say It: I’m Arab and Beautiful,” or “My Palestinian Poem that The New Yorker Wouldn’t Publish,” the latter written on the occasion of the May 2021 assault on Gaza. A new book has just been announced for March, poems written mostly in these recent months, titled […]. Because there’s no way this series of posts can contain everything I will just point you toward a few books, places where reading may live. Textu is one of my favorites of Joudah’s work, inventing a form based on the beginnings of text messaging, the charge you’d incur if you exceeded 160 characters—a meeting point of poetry, capitalism, working life, intimacy, constraint, inspiration… Here are a few poems:

Do You Remember

that night the war ended

our weapons your war

the camp’s clinic was burned to the ground

our clinic your health

what had you secure-

ly there

Those who remain are

those who are maimed

the poem worked its fingers through your bones

Economy of charity

a lending being lent

your distance

away from here

CHAOS, CROSSING

Olivia Elias

trans. Kareem James Abu-Zeid

Poetry. World Poetry Books, 2022

THINGS YOU MAY FIND HIDDEN IN MY EAR: POEMS FROM GAZA

Mosab Abu Toha

Poetry. City Lights Publishers, 2022

To feature these two books I am going to borrow/feature this wonderful recent review, published in the Cleveland Review of Books and written by Conor Bracken, poet and translator based in Northeast Ohio and translator of Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s Scorpionic Sun. In this review, from July 2023, Bracken considers the technology of the (Palestinian) poem as operated by the American reader, and in his deep reading of these two works also offers some forms for reading: “What should a poem do? is a far less interesting question to ask than What questions does the poem rise, like steam or stink, from?:

What should a poem do? It seems, honestly, silly to ask, especially because I think Aristotle, not Plato, was right on this count. Instead of assuming some ideal exists elsewhere which all things are striving and failing toward, the things themselves will tell you. Which is to say, the poem will tell you what it should do, and that’s enough. But in reading Najwan Darwish’s introduction to Kareem James-Abu Zeid’s translation of Olivia Elias’s collection of poems Chaos, Crossing, I found myself at a crossroads. Darwish asserts—forcefully, and convincingly—that “poetry… is a form of salvation.” But if I agree with him here (which I do), how do I square this with my revulsion at versions of this same statement elsewhere? (I’m remembering, among other schlocky instances of this kind of poetry sermonizing, a certain poetry anthology-cum-memoir from 2017 called Poetry Will Save Your Life, which one reviewer likened to being “imprisoned in a poetry theme-park.”) Is poetry the life-preserver we all need as we’re tossed on the white-capped shallow seas of a crowded sped-up algorithmically curated world? Is it really the thing men die for lack of everyday, as William Carlos Williams had it?

I thought about this a lot as I was reading Chaos, Crossing, Elias’s English-language debut, along with Mosab Abu Toha’s Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, two recent collections from Palestinian poets in languages that are neither their first, nor their shared, language: Arabic. Both poets are motivated by a palpable urgency which grows out of their disparate experiences of the violent and continuing Israeli occupation of Palestinian land, as well as from a deeper belief in the value of poetry, not merely as an aesthetic playspace (there are flashes of play amid heavy subject matter) but as a kind of lyric technology that can short circuit or bypass the kinds of AI-driven surveillance and PAC-funded mindmeld that continue to allow Israel to maintain the current apartheid state of affairs when it’s not actively expanding it. The stakes in both collections—poetically, politically, personally—are high. And the choice by both poets to write in languages that face a different audience than their “home” one suggests that both are turning to a wider congregation, not just the choir. This makes some sense. Srikanth Reddy notes, in a recent introduction to an issue of Poetry Magazine on exophonic poetics, that “[the] work [of exophonic poets] asks us to think deeply about language and identity, assimilation and acculturation, and the histories of collective violence, trauma, and displacement that have shaped our modern world.”

[Read more here…]

Mosab Abu Toha has just published an essay on his family fleeing the violence in Gaza and how he was detained by the IDF as they tried to make their way to safety—please read it, here in the New Yorker: “A Palestinian Poet’s Perilous Journey Out of Gaza.”

From Olivia Elias’s Chaos, Crossing, trans. from the French by Kareem James Abu-Zeid

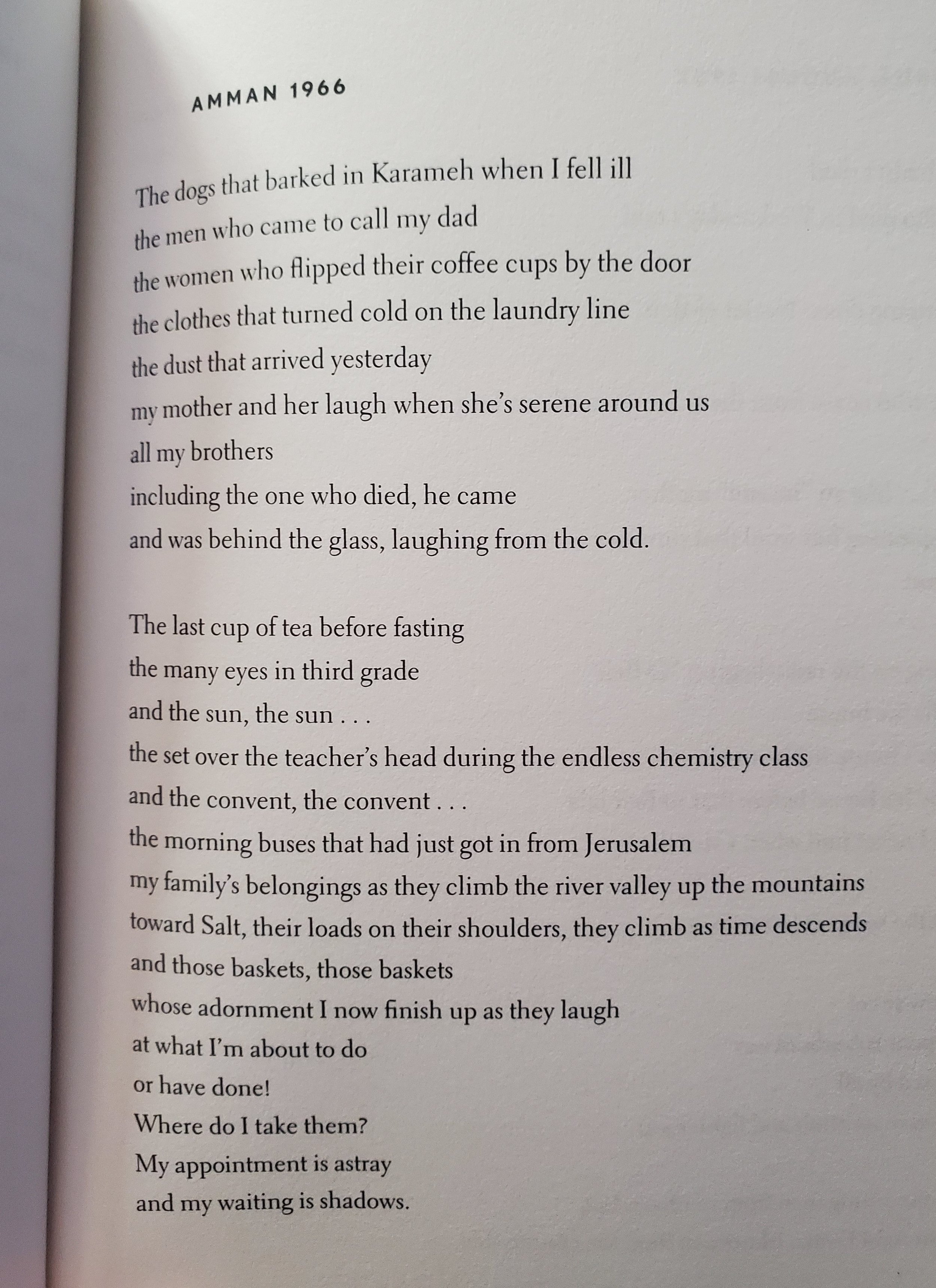

LIKE A STRAW BIRD IT FOLLOWS ME, AND OTHER POEMS

Ghassan Zaqtan

trans. Fady Joudah

Poetry. Margellos World Republic of Letters / Yale University Press, 2012

DESCRIBING THE PAST

Ghassan Zaqtan

trans. Samuel Wilder

Novel. Seagull Books, 2016

THE SILENCE THAT REMAINS: SELECTED POEMS

Ghassan Zaqtan

trans. Fady Joudah

Poetry. Copper Canyon Press, 2017

The work of the Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan (b. 1954) is less well known in English than that of Mahmoud Darwish, who was roughly his contemporary and commonly referred to by such terms as the “Palestinian poet par excellence.” (Indeed I have not highlighted Darwish’s work in these posts because it is already well known—though I recommend it extremely.) Zaqtan’s work is a favorite of mine. And he and Joudah seem especially well-matched as poets meeting in translation.

I’ve written about his books several times. From a review of The Silence that Remains:

“As if we had been there”: this line guides us into Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan’s newest volume in English, our presence remaining in the subjunctive mood. That we are as if there attests both to our own status—as readers of literature in translation—and to the displacements within history and memory given form in this poet’s magnificent work. In these poems, any event, any place, any memory bears the shadow of the subjunctive: of the history that didn’t occur; of what is no longer ours; of how relentlessly memory transforms presence into absence. This shadow—as if—defines what, in the light of any moment, we may know. The line quoted comes from the poem “A Swallow”: “As if we were together / as if we had been there / with the dead who are there / as if over there.” This stanza considers the role—the place?—of the poem: as if a poem could offer a togetherness that wasn’t, a presence that is no more, in a place lost then or now; even the absence of the dead isn’t here. In these swift lines, we glimpse the knowledge of the fleeting, of the less-than-present, to which Zaqtan’s work is dedicated.

The Silence That Remains, Fady Joudah’s translation of Zaqtan’s earlier work—with selections covering 1982 to 2003—was published this summer by Copper Canyon Press. This is Zaqtan’s third appearance in English: Like a Straw Bird It Follows Me, Joudah’s translation of Zaqtan’s more recent work, won the international Griffin Poetry Prize in 2013. The two volumes illuminate one another, each helping us to read the other: the unsimple spareness of the earlier poems; the suggestive, expansive precision of the later, such as the gorgeous “Pretexts” or the long poem “Alone and the River Before Me.” Describing the Past, a novella translated by Samuel Wilder, appeared from Seagull Books in 2016—an intricately elusive narrative set in the Karameh refugee camp, where Zaqtan himself was a child, before its destruction by Israeli forces in 1968 (Zaqtan was born in 1954, in Beit Jala, his family refugees).

[Read more here…]

And a review of Describing the Past is here. If you don’t know Seagull Books’ series of literature from the Arab World, find it here—a wealth of new work seems to have arrived since I last realized, including several works by Zaqtan: Where the Bird Disappeared and the forthcoming Strangers in Light Coats.

*

I’m going to conclude this series by gesturing outward toward everything it couldn’t include. If you have not yet read any Darwish, perhaps you might start with Memory for Forgetfulness: August, Beirut, 1982 (trans. Ibrahim Muhawi). Or you might start with one of the three translations into English of his unforgettable long poem “Mural” (or read them all, it is worth it). You might read the fiction of Randa Jarrar. George Abraham’s poetry collection Birthright. The poetry of Naomi Shihab Nye. The work of Arab American poets Hayan Charara and Philip Metres engaging with questions of empire, identity, and Palestine. The anthology Extraordinary Rendition, edited by Ru Freeman. The work is alive and proliferates in our reading…

—Hilary Plum, h.plum [at] csuohio.edu