SINK: An Interview with Anisfield-Wolf Fellow Joseph Earl Thomas

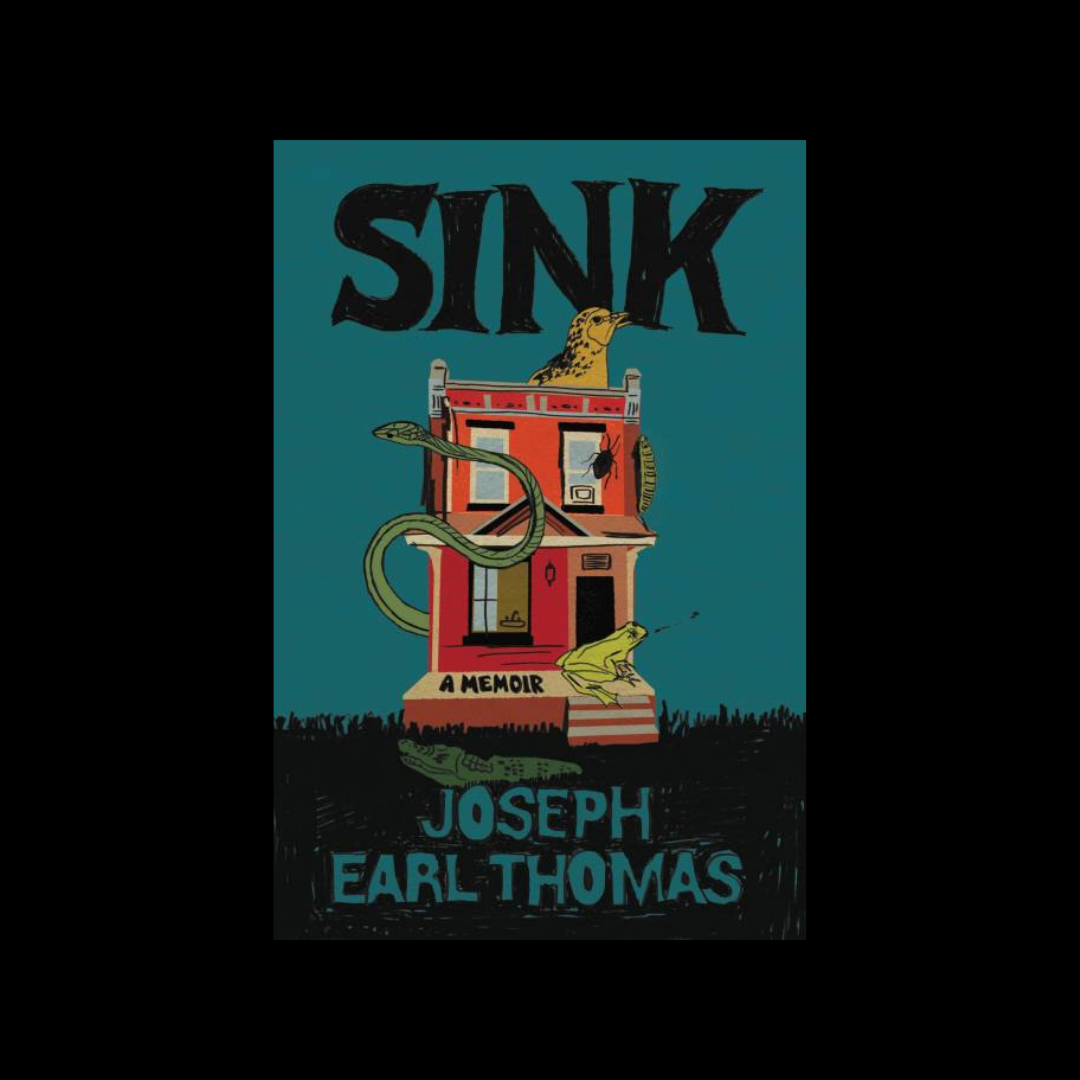

This fall, Joseph Earl Thomas joined the CSU Poetry Center as the 2022-2024 Anisfield-Wolf Fellow in Writing & Publishing. A newcomer to Cleveland, we thought it only right that he sit down for a warm welcome interview with a lifelong Cleveland resident, our own Joey Rooney (that’s right, Joey & Joey). Joseph and Joseph discuss Joseph’s hopes and dreams for Joseph’s time in this new city, as well as Joseph’s forthcoming memoir, SINK, which is narrated by Joseph in the present, who goes by Joey in the book, but who is really Joseph in the past. Wait.

Everyone in the NEOMFA program and at the Poetry Center is delighted that you’re joining us as the new Anisfield-Wolf Fellow in Writing & Publishing! Have you had the chance yet to acclimate yourself to the literary and cultural scenes in and around Cleveland State? What do you hope to experience as a fellow over the next two years?

I’ve always enjoyed theater but I’ve been thinking about it a lot more recently. The theater scene in Cleveland is a lot, and way more accessible than anywhere else I’ve ever been. I’d like to see as many plays as possible in the years to come. I’m also one of those people who doesn’t like to jump into anything without having a deeper comprehension of how it gets made, or how the work is done, so I hope to enter the theater space in some other practical, material ways as I return to writing a play I’d had on my mind for quite some time.

Your debut memoir SINK is being published by Grand Central Publishing in 2023. What influence, either internal or external (or both), inspired you to write a memoir, and what do you hope your readers will take away from Joey’s—your—story?

I think that in the African American Literary tradition, nonfiction and narratives about one’s own life experiences have always been important, even if we think about the shift to mostly novels in the post-World War II climate (especially during COINTELPRO), so there’s one reason why it seemed a natural choice. And perhaps because of this, and my own entry into a literary landscape where I don’t see genres as being too different outside of marketing materials it also seemed like a natural choice. I don’t really think there’s anything you can’t say or do in nonfiction, though I think maybe the politics and readership are a bit different from genre to genre. I’m really interested in detail, and material substance, and so it felt vital for me to claim, up front, everything, rather than what felt easier at times—to sublimate everything into fiction. Though I feel like all influences are both internal and external, everything is real and fantasy at the same time, and there’s no escaping that I’m also writing a novel—which is a whole other story.

You choose to narrate SINK predominantly in the third person, referring to yourself as “Joey” throughout. What does the third-person perspective do for your narrative that a first-person perspective would not? Toward the end of SINK, you transition into the second person, addressing readers as if they are you; and you, they. What effect do you envision this “as-if” technique having on your readers?

SINK has gone through revisions in pretty much every tense and perspective at this point. It’s been good practice, I guess. But I also think that the third person is historically the most novelistic and provides for the widest range of freedoms in a narrative that is also hyper focused on interiority. In writing SINK, or anything I do at this point, I try to be honest about the difference between the character then, and myself now, without the intrusion of my kind of pontificating adult self to correct the messiness, to impose order on all kinds of problematic thinking for my own or for the character’s protection, or to foreclose thoughts about the world that were intuitively useful as a child that many of us have absorbed as “normal” by the time we’re adults. Third person, and then second became the most valuable way to explore childhood uninterrupted, and then to bring someone else as close into that world as might be possible towards its termination.

How did you decide what memories, what vignettes, to include in SINK? Were there some potential vignettes that, for one reason or another, didn’t make the cut?

This is a great question. And maybe we could write a whole critical book about memoir beginning with this question, but yeah, I would say most things didn’t make it in, or can’t make it into a memoir for it to work. I began with my earliest memories and to some extent those that could be verified, mostly through my sister. What I also did in choosing what to include was to highlight primarily situations that happened repeatedly. If an event occurred only once, it was less likely I would include it in the book. I wanted to get a sense of the quotidian rather than the spectacular, as those are primarily the things that a life consists of. Some of the biggest suggestions from my editor Maddie were cutting sections that were essentially doubled explorations of sex, violence, or joy that overlapped earlier sections of the book without any significant difference.

You’re currently writing a novel, God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer, and also a collection of stories, Leviathan Beach. How does the process and craft of writing a novel differ from the process and craft of writing a short story or even a collection of short stories?

Apparently, I can get into more trouble for saying things that people don’t want said in a novel than in a memoir, which I found . . . interesting. Suffice it to say, the novel plays around with, or teases autofiction and speculative realism, and to a lesser extent fantasy too, where the stories primarily live. I think what people tell me about writing a novel is that there’s supposed to be more freedom but I haven’t found that to be true at all. So far I’ve been thinking of the novel having more restrictions, but trying to find fun ways to toy with those restrictions and a certain kind of history involving narrative expectation. I think the process is mostly different because of the material conditions of my life though. When I started SINK, so many years ago, my twins, who are now 5, weren't even born yet, and my two older kids were at a point where they’d developed some autonomy of play, but weren’t all that interested in what I was doing, nor did I work from home at the time. And for some of the writing of SINK I was in an MFA away from my family and just driving back and forth to Philly. Now I’m a single parent mostly working from home, reading, writing and teaching, so they think I’m just ready to play 24/7 (I kind of am so I’m often behind) and we’re a house full of gamers, 4 of whom attend three different K-12 schools with all the attendant considerations that come there.

When you’re not writing and reading, what do you like to do in your downtime? Any hobbies or pastimes?

All the things really. Basketball (more in the summer), videogames (more in the winter), amateur skateboarding, guitar (my son plays drums and my daughter sings so they want to make YouTube videos . . .), running (with or without doggies), and then I’ve started watching professional esports, particularly Pokémon where I eventually wanna compete.

Joseph Earl Thomas is a writer from Frankford whose work has appeared or is forthcoming in VQR, N+1, Gulf Coast, The Offing, and The Kenyon Review. He has an MFA in prose from the University of Notre Dame and studies English in the PhD program at the University of Pennsylvania. His memoir Sink won the 2020 Chautauqua Janus Prize and he has received fellowships from Fulbright, VONA, Tin House, and Bread Loaf. He’s writing the novel God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer, and a collection of stories, Leviathan Beach, among other oddities.

Joey Rooney is a writer of fiction and poetry and a first-year student in the NEOMFA Program. Born and raised on the west side of Cleveland, he received his MA in English from Case Western Reserve University and his MA in Theology and Religious Studies from John Carroll University.